Penned by Rashida Jones, Celeste

and Jesse Forever, co-starring Andy Samberg, is a cute, sincere, and

occasionally funny romantic comedy. Unfortunately, it is anchored by a messy

script and kitchen sink direction by Lee Toland Krieger, who can’t decide if

he’s shooting a Kate Hudson rom-com, or something more French New Wave.

Celeste (Rashida Jones) and Jesse (Andy Samberg) are a divorcing couple

still living together as best friends. This freaks out their friends, and

clouds their own feelings for each other. So, they work to find themselves by

finding happiness with other partners. When Jesse knocks up Veronica, a

look-alike foil for Celeste’s type-A “Betty,” Celeste is forced into a lot of

self-examination. The plot is very similar to the Greta Gerwig rom-com Lola Versus, which was released around

the same time, and I don’t mean that as a compliment.

Two things really bugged me about this movie. First, most of the drama

takes place off screen, requiring lots of expository dialogue, inevitably

followed by emotional reactions to situations we were not allowed to see. Relying

on all this explanation wastes any goodwill the stars' chemistry creates in the

early moments, makes the movie feel too long (at only 92 minutes), and ruins two

strong climatic moments.

The other thing annoying me was how Jesse is missing from the

self-examination storyline. After the film gives him a few moments away from

Celeste, it abandons him, depriving us the opportunity to see how a man in his

situation deals with the frustration and heartache of genuine separation.

Celeste becomes our sole focus character, and while Jones gives the role her

all, it’s not an uncommon role in romantic films these days; she’s a career

minded woman in love with a man child she is trying to change, but needs to

have a change of heart before she can either truly love him, or love him enough

to let him go. This is a cliché, but the only thing keeping the film from being

loathsome is the idea that we’re seeing this relationship at its end, and that

Jones has such incredible charisma. Had the script invested more time

paralleling Jesse’s growth, instead of dealing with 99 percent of it off

screen, Celeste’s journey would have had more emotional impact. I imagine the

rough draft of the script did this, but time and budget probably left several

choice scenes on the cutting room floor. If so, the film is lesser because of

it.

This saddens me. I wanted to enjoy Celeste

and Jesse Forever, but while it

shined in individual moments, and the cast’s chemistry was fun, the end result

was a squandered romance.

Smashed ***1/2 (2012) – dir.

James Ponsoldt

Pure and simple, Smashed is

an actor’s showcase. Mary Elizabeth Winstead and Aaron Paul take what were mere

sketches of characters and imbue them with remarkable humanity and passion.

What they accomplish here is important because on the surface, Smashed is quite unremarkable. Kate

(Winstead) is an elementary school teacher who comes to discover she is an

alcoholic. Charlie (Paul) is her equally alcoholic husband. Their world turns

upside-down the moment Kate decides to go to AA at the behest of a co-worker

(Nick Offerman) who recognizes addiction when he sees it. Kate’s choice is

predictable, as is much of the film’s thin story, but Winstead’s commitment to

her character’s journey makes the film powerful and riveting.

Films about overcoming addiction are not usually that interesting,

mostly because the story rhythms are so contrived, and because the victory at

the end is overshadowed by the exploitative elements of the initial fall. The

best decision that writer/director James Ponsoldt makes here is in making this

a story about the way being sober affects marriage. The moment Kate chooses

sobriety, her husband becomes her enemy whether he knows it or not. His

presence is a constant reminder of who she was, and who she is worried she

might still be. It’s a battle of worldviews, one cancerous, and one on

remarkably shaky ground. Winstead and Paul always play the notes with such

honesty that we feel like we’re watching the collapse of something real.

Rust and Bone*** (2012) –

dir. Jacques Audiard

Rust and Bone is a French

neo-realist film in the tradition of Italian films like Bresson’s Pickpocket and de Sica’s The Bicycle Thief, only done in a more

modern, independent film style. The pacing of the plot unfolds at a snail’s

pace until suddenly you’re struck by a moment of remarkable emotional impact.

It is the story of a wayward boxer named Ali (Matthias Schoenaerts) who is trying to

figure out how to be a father and a man; and about a woman, Stephanie (Marion

Cotillard) who is rediscovering what it means to be a woman in the aftermath of

a horrible accident that takes her legs. The fact that their lives cross at all

is a wonder, but their path to love is full of self-discovery.

Cotillard’s performance is beautiful, especially in the early going

after she loses her legs. The scene in which Ali takes her swimming in the

ocean for the first time since her accident is overflowing with hard won joy.

Her Stephanie is every bit as much a fighter as Ali, and she gains her inner

strength from his physical strength. When she’s on screen, the film is

powerful, electric, and real.

Unfortunately, it’s the scenes with Schoenaerts that seem to drag the

film at times. Ali is the traditional silent type – he seems fashioned after

Anthony Quinn’s Zampano in La Strada

– and while Schoenaerts plays silent and brooding well, he lacks nuance in

scenes when basic brutality is not enough. His scenes opposite his sister are

almost excruciating to watch, especially when compared to his scenes opposite

Stephanie.

When Rust and Bone is good,

though, it’s often great. Audiard goes to great lengths to connect us with

these characters, so whenever he allows for deus

ex machina contrivances, we are still remarkably affected.

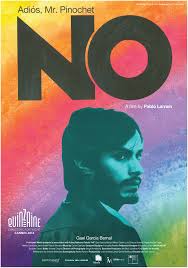

No ***1/2 – dir. Pablo

Larrain

American films are all about heroes. Individuals rise against the

opposing forces of government, society, family, conspiracies, etc. to overcome

great odds and establish a better, newer order. The heroes of American films mainly

stand for freedom, individuality, and capitalism. In foreign films, though,

there is often a different concept of what a hero stands for. No, the story of the 1988 campaign

against the brutal dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet in Chile, may be a Spanish

language film, but it is decidedly American in attitude and structure … at

least until the end.

Our hero is Rene Saavedra (Gael Garcia Bernal), a rising star in the

world of Chilean advertising. He is approached by a member of the “No” campaign

against Pinochet to be their creative supervisor. Rene decides to join the

cause after he witnesses his estranged wife, Veronica, get beaten by police for

speaking out against the regime. His idea is to abandon the negative, fear

mongering principles of the current creatives and focus on a simple concept:

happiness. His “Chile: Happiness is Coming” campaign – while initially controversial

for its very American-esque use of jingles, music video editing, staged images

of happy Chilean people, and positivity – becomes a such a threat to the “Yes”

campaign that Rene and the rest of his team soon find themselves fearing for

their safety and that of their families.

Rene is a hero in the American tradition. Among the many people

responsible for the “No” campaign, he is our focal point and savior. I think I

would have found the movie to be an effective, quality film if it had ended

with merely this thought in mind. After all, years of American movies have

trained me to feel good when individuals win out over totalitarian dictators.

But, (spoiler alert) the win over Pinochet leaves Rene in a world of

uncertainty, making him not just an individual, but a representative of the

soul of Chile itself. His ambivalence over his victory is best exemplified in

the final scene, which ironically displays what the future has in store for his

beloved country. Rene may be a hero, but he is a hero whose contribution to the

end of one regime may have contributed to the reign of an entirely different –

and possibly more nefarious – one. Most American films would be unwilling to

challenge its audience with ambiguity like this – our heroes may be dark and

conflicted now, but unless they are on cable network television shows, once

they decide to cross the threshold into adventureland, they are definitely not

ambiguous.

The look of the film goes to great lengths to highlight this. Director

Pablo Larrain decides to shoot the film in a 4:3 aspect ratio, and with a video

style that looks like we’re watching VHS tapes from the 80s. It’s a bold move

that pays off. The movie feels real and dangerous, like history itself.

I imagine this would be the time to call “bullshit,” but I suggest

watching No back-to-back with last

year’s Best Picture winner, Argo (a

movie in my year end top 10). The two films are about lone heroes who use the

media to deliver oppressed people from terrible dictatorships. Argo delivers on everything American

movies have represented over the last hundred-plus years (with one slight

exception involving its explanation of Iranian political history that does an

outstanding job of revealing the complexities of the situation the audience

finds the characters in). No uses the

American aesthetic and rides it to victory until it reveals that this aesthetic

was both the solution and the problem all along. Did Chile sell its

soul to the American devil of advertising, which promises happiness that it

ultimately cannot deliver?

No isn’t just a film about

Chile’s past, it’s a film about its present.

American Mary * (2012)

dir.Jen and Sylvia Soska

No matter how you slice it, American

Mary is an awful movie. To one end, it’s a pretentious rape-revenge story

that wants to seem like a profound feminist statement. To another, it takes an

intriguing premise for a horror film and pushes it to absolutely ridiculous

places. And, if that weren’t enough, it is a technical nightmare, with acting,

editing, and staging that should border on embarrassment for the filmmakers.

Mary is a pre-med student with financial problems. To solve her issues,

she decides to go to work at a strip club as a sexy masseuse, but winds up

getting herself involved in performing a back alley surgery on someone owing

the club manager some money. From there, she is hounded by a woman with a Betty

Boop fetish who wants Mary to do some experimental cosmetic surgery on a friend.

Eventually, Mary takes to liking the money and power she gets from performing

body modification surgery and decides to use her skills to get revenge on a

college professor who took advantage of her at a party.

American Mary suffers from the

childish narrative disease of “and then…” As in, “and then Mary was asked to

perform a creepy surgery to make a woman look like a doll, and then she was

raped by her professor, and then she was doing surgery on her professor, and then

the police were talking to her, and then…” Cause and effect plays little role

in this movie. It reminds me of when I started writing horror fiction as a

teenager, and would rush my way through all the important transitional scenes

in order to get to the “good parts.” This movie is a collection of “good parts”

with little else, meaning that there are no good parts, just moments of blood

and mayhem for their own sake.

It’s bad enough that the movie is a narrative train wreck, but it is

also so full of itself. The Soska sisters, who wrote and directed this, no

doubt thought they were making a profound statement about society’s definition

of women as sex objects, and embodied their free expression sentiments in the

form of their eponymous surgeon. Mary’s surgical acumen is supposed to bring

liberation to those she touches, and nightmares to all those who seek to

objectify her. But Mary is such a dull character, such an obvious symbolic

avatar that the overt symbolism is condescending, especially at the end when a

final shot of Mary reveals her to be yet another cinematic Christ figure.

I've spent too many words writing about this movie.

No comments:

Post a Comment